[Last updated 10/31: After re-reading the original version of this post and checking the data from the Statistics Department again, I realized I had misinterpreted a couple of numbers in the Herald article – which I guess illustrates why I wrote it in the first place… the Herald’s article is really not easy to understand. I have updated the post to reflect my current (hopefully correct) understanding.]

Well I wasn’t really planning on writing about trade (lots of other things buzzing around my mind), but the NZ Herald had a report yesterday on some data just released by the NZ Department of Statistics, and as they often do, numbers caught my attention. Here’s what the Herald had to say –

New Zealand’s annual traded surplus widened last month as the nation shipped more dairy products, logs and crude oil while a tepid domestic economy constrained imports.

The trade surplus was $921 million in the 12 months ended September 30, from a revised surplus of $892 million in the year through August, according to Statistics New Zealand.

The monthly traded deficit was $532 million, up from a gap of $413 million in August.

Exports in September rose 12 per cent to $3.16 billion, for an annual increase of 0.5 per cent to $41.8 billion. Monthly imports rose 9.1 per cent to $3.69 billion for an annual decline of 5.5 per cent to $40.88 billion.

… all of which kind of left me scratching my head. The fact that “the annual trade surplus widened last month” sounds like a good thing. The fact that “the monthly traded deficit was… up” sounds like maybe not such a good thing. And what are we supposed to make of the numbers themselves? Are they big? Small? The Herald really didn’t make much of an effort to help me figure out what the ‘take home’ messages should be. Yet I needed to know…

The idea of a trade surplus (or deficit) is straightforward enough – the difference between the total value of the country’s exports and imports over some period of time. Things can get a little more complex, though, because there are different ways of describing how these three measurements (exports, imports and their difference) change over time. In fact three different ways of comparing such measurements are used in the Herald’s article. Here’s what’s going on…

The Statistics Department calculates the value of exports and imports and the surplus or deficit they represent on a monthly basis. So we can use these numbers directly to compare values for the current month with those in the previous month. Given a specific set of numbers, we might conclude, for example, that imports are greater this month than last or that the surplus is smaller than last month etc.

Looking at the data on a month by month basis is interesting, but it has the disadvantage that the figures are likely to be influenced by seasonal factors. Consequently, it may be difficult to draw conclusions about overall longer term trends just by looking at the data in this way. An alternative is to add the values for each of the previous 12 months together and get a figure for the whole of the past year. Again, we can do this for either export or import values or for the surplus or deficit they produce. Once we do this, there are then two different ways that we might choose to describe how the resulting measurements are changing over time (actually there are many possibilities, but two are used in the data reported by the Herald).

One option is to take any one of these values, let’s say the surplus, calculated for the year that ended with the current month, and compare it with the corresponding value for the year that ended one month earlier. Note that together the two values we’d be comparing make use of data recorded over a total period of one year and one month, essentially by taking a moving sum of the monthly data. So the two totals each involve data for mostly the same months. If we were comparing the surplus for the year to September with the surplus for the year to August, for example, both values would contain data from October last year to August this year. The difference is that the total for the year to September also includes the data from this September, while the total to August instead includes data from last September.

What this means is that any difference between the totals for the year to September and the year to August are due entirely to differences between the data for the month of September this year and the month of September last year. Comparing the two total values is actually equivalent to comparing data between just those two months, September this year and September last year. So if, for example, the total (exports, imports, surplus or deficit) for the year to this September is X dollars greater than the total for the year to August, it means that the data for just the month of September this year is X dollars greater than that for the month of September last year.

Ok, I said before that there are two ways we can describe how the total data for one year changes over time. The second option is to take the total (again, exports, imports, surplus or deficit) for the year that just ended and compare it to the total for the year that preceded that one, or, in other words, the year that ended one year ago.

Obviously, this involves taking account of data recorded over a total period of two whole years rather than a year and one month. Why would we do this? Well, again, it helps to smooth out short term variations and gives us a better idea of longer term trends in the data. A sharp spike in (say) the deficit in one month may cause the deficit calculated for the year up to that month to rise compared with the month before. But if the overall trend over the past several months has been a decreasing deficit, it may be premature to conclude that the trend we’d been observing has been reversed, just based on that one month. The upward spike may be simply a short term anomaly and it may turn out that subsequent data will show that the overall trend continues to be one in which values are decreasing over time. Comparing totals over a year for two consecutive years is a more reliable way to identify what that long term trend is.

Ok, let me summarize –

- there are three different types of data involved in the Herald’s report – export values, import values and the difference between them, which can be either a surplus or deficit.

- any of this information can be calculated for either a single month or an entire year (and of course there are any number of other possibilities as well, but these are the ones the Herald article is concerned with).

- any value that has been calculated for a whole year (exports, imports, or surplus/deficit) can be compared in time with either the year that ended a month ago or the one that ended a whole year ago.

And so to the data… What is it that the Herald is reporting? The following –

- For just the month of September 2010, total exports were valued at $3.16 billion and imports at $3.69 billion, resulting in a deficit for that month of $532 million.

- The deficit in August was lower than September at only $413 million. The Herald didn’t report the export and import values for August, but the Statistics Department’s data shows that exports were very slightly lower than September at $3.15 billion, while imports were significantly less than September at $3.56 billion.

- The total value of exports over the whole year to September was $41.8 billion, while imports for the same period were $40.88 billion. This resulted in a trade surplus for the year of $921 million. Note that we had a surplus for the year to September even though there was a deficit of $532 million for the month of September by itself, because there were some good months during the rest of the year. Was September itself a good month or bad? To the extent that there was a deficit for that month, you might say it was bad. However if we recognize that there is always some seasonal variation over the course of a year, we can’t really conclude that without looking at the year as a whole. And what we find is that the year as a whole was ok. But really, we want to know more than that – based on the figures for September, are things getting better or worse?

- The answer is that the trade balance seems to be getting better. While we had a trade surplus of $921 million in the year to September, in the year to August the trade surplus was lower, at $892 million – not by much, but lower nonetheless. Note that the surplus for the year to September got better even though the deficit in September actually deteriorated from the previous month (remember, it went from $413 million to $532 million). What this implies is that the September data, though poor (in the sense of being in deficit), was better than it was a year ago in September 2009. We can confirm this from the Statistics Department’s data: Table 1 in this Excel spreadsheet available here shows that while the deficit for September 2010 was $532 million (column J, row 60) as reported by the Herald, the deficit in September 2009 was even worse at $561 million (column J, row 47).

- As well as wondering whether the surplus has improved, we’re also interested in knowing why it has improved. Does it reflect an improvement in exports or a reduction in imports, or both? The Herald doesn’t really provide as much clarity on this point as we might hope. They do note that exports in September rose 12% to $3.16 billion while imports rose 9.1% to $3.69 billion. However, they don’t make it clear that these numbers represent the change from September last year, rather that from August this year. This is what we need to know to understand that these numbers do actually relate to the reported improvement in the surplus. Remember that that improvement related to the total surplus for the year to September ($921 million) compared with the total for the year to August ($892 million). And the difference between those two values is the same as the difference between the values for the month of September this year and September last year. The 12% increase in exports amounts to $335 million while the 9% increase in imports represents $306 million. So it is the fact that exports have increased from one year ago more rapidly than imports that accounts for the fact that the surplus has increased by 335-306 = $29 million from $892 million to $921 million. This presumably is what the Herald is referring to when it says that “New Zealand’s annual traded surplus widened last month as the nation shipped more dairy products, logs and crude oil while a tepid domestic economy constrained imports.” However that statement on its own is arguably a little misleading or at least confusing given that the trade balance for the month it’s referring to was actually in deficit and worse than the month before it.

- The Herald also cites two other numbers – an ‘annual increase’ in exports of 0.5% and an ‘annual decline’ in imports of 5.5%. They don’t make it especially clear, but these numbers represent the difference between the totals for the year to September and the totals for the year that ended one year earlier. It’s interesting that these numbers show a somewhat different trend compared with the change in the monthly values between September 2009 and September 2010, with exports increasing only very slightly and imports decreasing rather than increasing.

It’s a bit unfortunate that the Herald’s report doesn’t say more about the trends in exports and imports, since more information is actually available. The numbers that the Herald reports describe the differences in exports and imports between September this year and September last year – in one case the values in those specific months (increasing 12% and 9% respectively) and in the other the total over the year ending at each of those months (increasing 0.5% and decreasing 5.5% respectively).

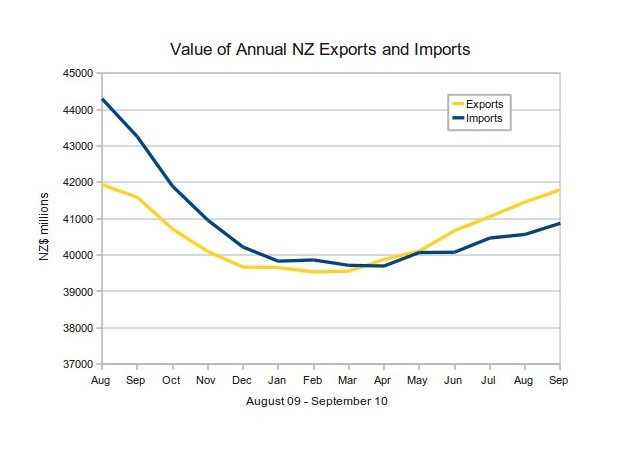

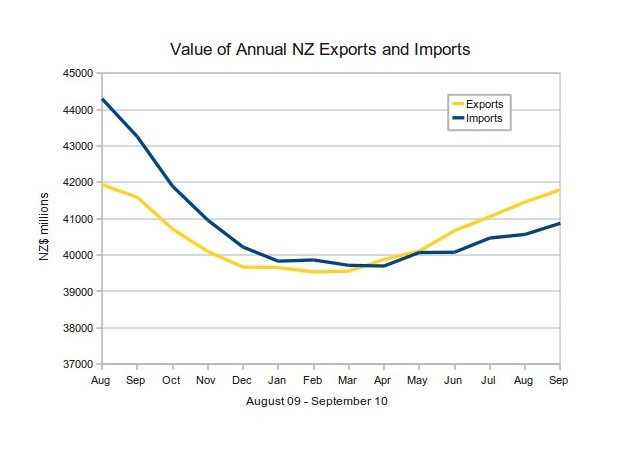

However the data released by the Statistics Department also tell us something more about what has happened over the course of the year in between those months. To illustrate, the chart below plots exports and imports calculated over multiple periods of one year ending at each month between August last year and September this year. The numbers are derived from column G in Table 1 of the same spreadsheet I mentioned before. The spreadsheet only provides values for individual months, so I calculated the sum over each 12 month period myself.

The chart shows that from a significant trade deficit in August 2009 (which is not mentioned in the Herald article), there has been a consistent improvement in the trade position over the past year. Initially, exports and imports both fell away towards the end of last year, but imports more than exports. Subsequently, exports and imports have both started to increase, and exports more than imports, leading to a growing surplus. Note that the vertical scale doesn’t start at zero, so the magnitudes of deficits and surpluses look a little exaggerated. In August last year, the deficit was 5.6% of export receipts, while in September this year the surplus was 2.2%.

There is also another way we can get some perspective on the size of the trade surplus and that’s to compare it with gross domestic product. The latest available figure is for the year to June this year – NZ$ 133 billion (source: Table 2.1 of this spreadsheet, available here; add the last four quarterly figures shown in column P). This puts the total export and import figures in some perspective: the roughly $41 billion for each is around 31% of GDP, and the trade surplus of $921 million for the year to September represents about 0.7% of GDP. In other words, it’s pretty small.

Part of the reason that I take interest in the trade figures is because they form part of the current account. So another question I have is how does the size of the trade surplus relate to the size of the current account? Well, this post is already way longer than I expected it to be. So that question will have to wait for another time.